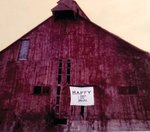

While the barn on the Huber’s Ferry Farmstead Historic District was built to last with German engineering, time eventually caught up and a combination of high winds and age resulted in its collapse …

This item is available in full to subscribers.

We have recently launched a new and improved website. To continue reading, you will need to either log into your subscriber account, or purchase a new subscription.

If you are a current print subscriber, you can set up a free website account by clicking here.

Otherwise, click here to view your options for subscribing.

Please log in to continue |

|

While the barn on the Huber’s Ferry Farmstead Historic District was built to last with German engineering, time eventually caught up and a combination of high winds and age resulted in its collapse just before noon on March 15.

“It had been leaning for a while,” said owner David Plummer, who with his wife, Barbara, ran the very successful Huber’s Ferry Bed & Breakfast on the farm from 1998 to 2015. “That barn was part of our operation.”

Weddings and receptions were held there, and the barn was repaired by Cliff Wagner, who put braces back in the hayloft, which gave it another 20 years of life.

Plummer said he is impressed with the way the barn was constructed, which undoubtedly accounted for its long life. “Ben Forck and his brothers were hired to build the barn, and there’s a beam in the barn with ‘BF’ engraved into it that’s still standing. It’s one of the few beams still in place since the collapse.”

Ben, JH, and Anton Forck lived in Taos, and construction of the barn took place in 1894. It was widely believed to have been the largest barn in Osage County.

As part of a National Register of Historic Places registration review in 1998 by Architectural Historian Debbie Sheals, a private consultant from Columbia, it was noted the barn was set into the slope of the hill, on a foundation of very large squared limestone blocks. Stepped stone retaining walls at the basement level provided clearance for wagon doors which were located on the south ends of the lower gable end walls. A second set of wagon doors on the main level, which was level with the house yard, were set just north of the center axis. Only the west door of the upper set was level with the ground; the east door on that level was presumably installed to create a cross-breeze for the threshing floor within.

The siding on the barn was yellow pine lumber cut from the forests in the Vienna area and the interior of the barn had three main levels. The basement level, which was used to shelter livestock, was partially below grade. There was a stock pen in each rear corner, with a haymow and open area between. The stock pens had small windows in the foundation walls, and both retained early or original grain and hay racks.

Huber family history holds that milk cows were kept in the western stock pen, and beef cattle in the other. Hogs and sheep were presumably sheltered in the open center space, as well as in a long shed addition that once ran along the lower south wall. A double set of stairs in the middle of the room provided access to the main floor; one set led from the haymow, and one from the open area.

A wide aisle ran along the south edge of the basement level, between the wagon doors. There were two sets of wide wooden pulleys mounted on the ceiling in that area, which are said to have been used to hang the wagons from the rafters during the winter months. The area directly above the aisle was a hayloft that sat higher than the main floor level, creating a taller ceiling in the basement aisle. Openings in the floor along the south wall of the loft allowed hay to be tossed directly down into the basement aisle. There were also trap doors further back, which allowed farmers to transfer feed to other parts of the basement.

The main level of the barn contained a central wagon drive, horse and mule stalls, harness storage, and the raised loft. The wagon drive ran along the long axis of the building and was reached via a set of double doors on the west wall. The stalls that lined the north edge of the barn were each equipped with an exterior door and screened transom window.

The central wagon drive appears to have been used as a threshing floor when the barn was new. The floor had an extra layer of floorboards situated to catch the prevailing westerly winds. The open area south of the wagon doors had pegs and other harness storage equipment, as well as open doorways to the raised hayloft along the south wall.

Access to the other parts of the barn was provided by three sets of stairs located on the north side of the threshing area. Large trap doors covered the two sets of stairs to the basement, and a longer, open flight led up to the main hayloft above. There was a large open hayrack just east of the stairs which provided access between the hayloft and the main floor. The base of that rack was close to the horse stalls as well as the small trap doors into the basement level, making it easy to transfer hay from the loft to all parts of the barn.

The hayloft was the largest space in the barn, rising nearly three times as high at its peak as the ceiling of the main floor. The loft was vented at the ridge by the monitor roof, and there were two large sets of swinging doors beneath the hay hoods to allow easy loading of hay from outside the building. The early or original track for the hay forks ran along the ridgeline. The secondary loft in the south part of the barn also opened onto the main loft. That area had its own track, which ran between a pair of smaller doors set high in the side walls. Neither set of hay forks had survived at the time of the review in 1998.

The main loft also had a large open frame structure along the area near the stairs, which would have served as a catwalk to access the top of the hay stack when the loft was full.

During her review, Sheals noted the barn appeared very much as it did during the period of significance and exhibited a high level of integrity of design, materials, workmanship, setting, location, feeling, and association.

Keith Huber grew up on the farm and was very familiar with the barn. “They really constructed these buildings to be durable,” he said. “It’s a credit to the German engineering of the time.”

A paint job in 1981 required 90 gallons.

BEGINNING OF THE FARM

The Huber's Ferry Farmstead still features the large brick farmhouse, built in 1881 by the son of German immigrants, and occupied by three generations of his family. Owned by the Huber family from the earliest days of settlement until 1990, the property today looks much as it did when William Huber and his family managed both the ferry and the farm.

Sheals in her review of the property noted that one of the earliest German settlers in Westphalia was Frederich Charles Huber, a 23-year-old from Paderborn, Westfalen, the same area from which Westphalia's first settlement party came. Huber came to Missouri the same year that Westphalia was founded and apparently made his home in that community, as it was there that he was married a year later. Huber's first wife, Christina Schroeder, died in an accident after just two years of marriage, and in 1840, he married Elizabeth Luekenhoff, who was also born in Westfalen. Huber did well in his new homeland; early deed records show many land purchases in his name, along with at least one deed of trust that indicates that he was wealthy enough to lend money to others as well.

Huber moved out near Lisletown within a few years of coming to Missouri, and it was there that his family remained for more than a century.

Sheals recorded that although the warranty deed solidifying his original purchase of the land on which the farmstead is located was not found, it is believed that he moved to the area in the early to mid-1840s, possibly just after his son William was born in 1844. It seems quite likely that the family was there by 1848 when Huber paid $300 for a quitclaim deed that cleared the title of land around the current farmstead.

STARTING A FERRY BUSINESS

By the late 1840s, he had also established a business that would remain in his family for the better part of the next century. Court records show that he was operating a ferry in the Lisletown area by 1847. The ferry was described in one historical account as "a key ferry operation on the Osage River, servicing an east-west road, that by 1837, was the main route between St. Louis and Jefferson City," according to Sheals.

The ferry business was, from the very beginning, a family affair. Huber's wife, Elizabeth, was granted the business license after his death in 1850, and from there it passed on to his son William L. Huber, and then his grandson, Charles Joseph. It was also under the ownership of William L. Huber, the fourth of Frederick Charles and Elizabeth Huber's five children, that the house was built and the farmstead took its current form.

William L. Huber was born in Westphalia in 1844, served in the Union army during the Civil War, along with his older brother, Joseph, and fellow Westphalian Heinrich Bruns. They fought at the Battle of Iuka in Mississippi when the latter was killed on July 7, 1863, according to a “History Matters” piece written by Dr. Gary Kremer and published May 23, 1999, in the News Tribune.

William married Westphalia native Mary Althueser on May 15, 1868, in St. Louis.

The house and farmstead served not only as the headquarters for the farm and family life, but it was also the center of operations for the ferry business. William Huber operated the ferry for more than 40 years, often taking sole responsibility for both the ferry and the farm.

Dr. Kremer, now the executive director of the State Historical Society of Missouri, noted in his article that according to a journal kept by William Huber, in 1871 he charged $2 to transport a wagon and two draft animals, while a “man and a horse” cost 25 cents, and a “footman” was charged 10 cents.

According to an article written by Joe Welschmeyer and published in the UD on Sept. 27, 1978, in the 1880s, the Huber home included soft red brick that was made at the state penitentiary and brought to the landing by steamboat. Others were made at a brick kiln in Westphalia.

It was under William L. Huber’s ownership that the captain's roof (widow’s walk) was added to the house around 1900 to provide an even more sweeping view of the countryside.

The broader view would have allowed him to see approaching ferry passengers, and to watch for the arrival of steamboats on the Osage River.

One of those steamboats was his own. In addition to running the farm and ferry, he was a partner in a local packet company, which operated the steamboat "Ramona,” and traveled on the Osage River, from Osage City to landings downstream, including Huber’s, Castrop’s, Castle Rock, and Bloody Island. Wheat and hogs were among the most important commodities shipped by steamboat, Welschmeyer wrote.

Huber partnered in that venture with local steamboat Cpt. Henry Castrop, a younger man who was also the son of German immigrants.

When William L. Huber died in 1914, Charles Huber II took over the family’s ferry business and saw it thrive.

Welschmeyer noted in his article that during this time, not only was there an increase in the number of singles and team wagons, but the automobile was boarding the ferry. Before this, a trip to Jefferson City would take half a day.

Ironically, the addition of automobiles would eventually lead to the decline of the ferry business on the Osage River.

In 1917, the State Highway Department had its beginning, along with federal aid to start new highway construction. In 1920, a bond issue of $60 million was approved and the next year, the Missouri legislature passed the Centennial Road Law and the State Highway Commission to plan and build Missouri’s highway network.

The Osage River bridge construction began in 1921 and continued into the summer of the following year. It stood for many years until the current bridge was built.

Hwy. 50 was paved through Osage County in 1931, followed three years later by Hwy. 63.

Following the death of Charles Huber II in 1955, the farm passed into the hands of Carl Huber, who with his wife, Goldean, lived on the property and ran the farm for another 25 years. Carl died in 1983, and Goldean stayed on in the family house until 1990 when the house left the Huber family for the first time in its long history.

“Grandma built a new house in 1990 because the big house took too much effort to maintain,” said Keith Huber of Goldean Huber.

NEW OWNERSHIP

The Huber farmstead is situated atop a steep bluff that commands sweeping views of the surrounding countryside. It is located near the junction of the Maries River, which runs just a few hundred yards north of the house, and the larger Osage River, which borders the western edge of the property, at the foot of a steep bluff.

“I wanted to retire to someplace with a view,” said Plummer, who spent six years restoring the property before opening the bed & breakfast.

The house, which faces west, is near the edge of the bluff and faces a drive that follows the path of an early road that led to the ferry landing and the road, which is now Hwy. 50. The house yard is delineated on the west and north by a low stone retaining wall which was originally topped with a white picket fence. Several early iron fence posts remain in place. The wall is constructed of massive stone blocks, many of which are three or more feet long and more than a foot wide. Most of the rock-faced blocks have carefully squared edges and are fitted tightly together. The wall also features stone gateposts on both the south and west sides of the yard.

Installation of new roofing was one of the first tasks to be accomplished during the rehabilitation of the house and barn, which began shortly after Plummer purchased the property in 1992.

When Huber’s Ferry Bed & Breakfast opened, David and Barbara Plummer offered an inn that was a “step back to a more peaceful, romantic time,” complete with a home-cooked meal every morning.

David and Barbara Plummer closed the bed & breakfast in 2015 due to health issues, and now, they simply enjoy the big home.